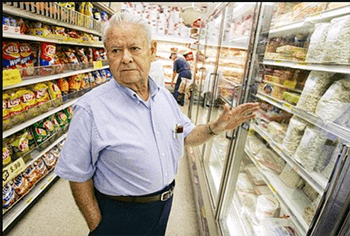

Earl Game

Game’s Farmers Market

Game’s Farmers Market

– By Dennis Hartig

That’s what everyone told Earl Game when the Commonwealth of Virginia gobbled up for a new highway the entrances and parking of his Newport News grocery, delivering a crippling blow to his popular business. You can’t fight City Hall.”

“You can’t beat them, Earl,” a chorus of naysayers warned him. “You’re wasting your time and money.”

Propelled by a strong sense of right and wrong, Earl not only beat them in court, but channeled his energy into the start of a political crusade that curbed — in ways big and small — the state’s exploitation of property owners. Earl was among the earliest leaders in the campaign to end eminent domain abuse in Virginia.

His battle began in 1998 when he got word that the plan for a six-lane highway to be called the Hampton Roads Center Parkway would eat up the front door to his grocery, Game’s Farmers Market. Its intended path closed three entrances, creating a nightmare for customs trying to drive in.

Just the electrical renovations — one of many burdens inflicted on the business — cost Earl $150,000. But for all the losses of property, damage and disruption, the state claimed it owed him but $25,000.

“I felt like I had no rights,” he said.

He retained attorney, Jospeh T. Waldo, of the law firm of Waldo & Lyle, to wage a long legal battle in court. And he got the local newspaper to pay attention. Its opinion writers castigated the condemnation as “highway robbery” and the agents of the state as “land sharks.” The public rallied to his side.

“I had to fight like a dog,” he said.

But he won a sweet victory. The jury decided that the state owed him $800,000, more than 30 times what it told him at the start was a fair price for his losses. But Earl wasn’t done. Wise now to the ways that eminent domain laws put property owners at a disadvantage, Earl decided to keep fighting, but this time by mobilizing public sentiment to move the General Assembly of Virginia into action.

With a $5,000 full page advertisement in the Newport News Daily Press, he launched a public education campaign. The ad invited citizens to a public meeting to learn about how their rights were being abused. In plain language, Earl made a compelling case for reform:

“No one wants to stand in the way of progress and it is inevitable that for the good of the public sometimes private property must be taken by eminent domain.

“But in Virginia something is terribly wrong when private property is taken by eminent domain. The laws are stacked in favor of the government and against the private property owner. All most citizens want is a level playing field where they believe they will get a fair opportunity to be heard and equal treatment.

“Today in Virginia that does not happen. When the government makes an offer for your property, or seizes it, you are not entitled to get a copy of their appraisal. The present laws do not even require that you be offered the fair market value of your property (yes Virginians can legally have their property seized and be offered less than the fair market value).

“In Virginia if the government seizes your property by eminent domain and the government makes a mistake on the value of your property, the private property owner must pay all the costs and attorneys fees even though the government seized the property and tried to underpay. “

The auditorium was packed. Local lawmakers saw the passion for change. They went to Richmond and persuaded their colleagues to study whether there was merit in Earl’s complaints. Earl was right, the study concluded and in 2001, the General Assembly enacted two modest reforms of eminent domain laws. It was only a start; year after year the changes kept coming, culminating in 2012 when the voters, in a statewide referendum, enshrined property rights protections in the State Constitution.

It started with one citizen.

Before his retirement in 2008, Dennis Hartig spent four decades reporting and editing for The Virginian-Pilot. As managing editor he directed reporting on eminent domain abuses and, later, as editorial page editor he crusaded for reforms.